June 2020

Accidents at or near KSBP

The recent accident in Santa Maria is a reminder that even though student pilots are by far the safest group of pilots, they sometimes have accidents too. When I was learning to fly there were two fatal accidents on takeoff from KSBP; I witnessed a ground loop; and I taxied past an airplane that had almost had it’s wing cut off a few hours before by another airplane. Surprisingly enough I finished my PPL.

While reading through last month’s articles I came across a mention of what is the largest fatal crash in the area. Pacific Southwest Airlines Flight 1771 when a former employee of the airline shot the two pilots. The plane crashed in San Luis Obispo County near Cayucos. All 43 passengers and crew aboard the plane died, five of whom, including the two pilots, were presumably shot dead before the plane crashed.

You can’t avoid accidents like that but since many of you haven’t flown due to the lockdown, it would probably be a good idea to go for a few training flights before you take anyone else up. I haven’t flown in the last three months so I went up to get current and I am glad that no one was with me to witnesss my sloppy flying. Reviewing the accident reports for local flyers might help you avoid an accident.

Stall-spins on Turn-to-Final

The Santa Maria accident on May 20, 2020 appears to be a stall-spin on final. The pilot pulled the parachute but was too low for it to be effective. It appears that he was on his long cross-country from Van Nuys and either did a touch and go or wasn’t comfortable with the first landing attempt and did a go around. We had been having Santa Ana like winds here for the past week; Weather Underground says that the wind was 8 gusting to 17 down the runway (RWY30), so that could very likely been a factor. The accident was at 17:43:00Z and the METAR says:

METAR KSMX 201751Z 29007G15KT

METAR KSMX 201851Z 31015G20KT

That shouldn’t be too bad since it was basically right down the runway. Kathryn’s Report has details of the pilot and pictures. The preliminary NTSB report has been issued but it has few details.

Fly the airplane all the way to the hangar.

We have been fortunate that there haven’t been too many accidents recently in San Luis. We’ve had a couple of gear up landings and ground loops recently, some of which didn’t make the NTSB list. The last fatal accident was in 2014. Just like the newspaper clippings, Oscar Bayer managed to make the list. He reported that during touchdown in the tailwheel equipped airplane, it bounced once, and as the airplane main landing gear made contact with the runway, the right landing gear strut collapsed. The pilot lost directional control and the airplane ground looped. The fuselage and right wing sustained substantial damaged.

The pilot of a Cessna 140 had a similar event. The pilot made an uneventful three-point touchdown. Thereafter, the airplane veered left, and the pilot applied rudder pressure and engine power to correct for the yawing moment. The pilot reported that the swerve happened so fast he was unable to take effective corrective action. Airplane control was lost and it nosed over. Thereafter, the airplane veered left, and the pilot applied rudder pressure and engine power to correct for the yawing moment. The pilot reported that the swerve happened so fast he was unable to take effective corrective action. Airplane control was lost and it nosed over.”

There were several more ground loops in the database including one pilot of a brand new Waco who totaled it.

Trent Palmer has a video explaining just why taildraggers have a tendency to go tail over teakettle while tri-gears do not.

Gear up landings are noisy but survivable.

In addition to Garrit’s Cessna 210 gear-up, there were three more that I know of. A recent one hasn’t made it to the database yet, there was one in 2018, and one of an early model 210 that sat on the ramp for months maybe 5 years ago.

One of the things that Austin stresses is that you don’t mess with anything in the airplane until you are off the runway and stopped. Then go through your after-landing checklist. Mine is BC-FLAGS, boost pump off, cowl flaps open, flaps up, lean for taxi, get some air in the cockpit, call ground, and change the squawk to VFR. On the planes I fly mistaking the gear handle for the flap handle would be difficult, but it is apparently easy to do in a Cessna 310 when Before exiting the runway, the pilot went to retract the flaps when he inadvertently raised the landing gear handle.

Hazardous Attitudes

The last fatal accident occurred just after takeoff when the pilot took off in his new-to-him twin-engined Cessna 337. On previous flights, the airplane’s rear engine had been “stuttering” as the throttle was advanced. The pilot was able to forestall the problem by advancing the throttle slowly; however, the symptoms had been getting worse. A maintenance facility at the departure airport attempted to troubleshoot the engine problem but was not able to resolve the issue. Thus, the pilot intended to reposition the airplane to another airport where a different maintenance facility had agreed to continue the diagnosis. He planned to fly the airplane in the traffic pattern, perform a touch-and-go landing, and proceed to the other maintenance facility if the airplane performed correctly. He had also made plans to depart that night on an important and time-sensitive business trip to Europe from an airport close to the second maintenance facility.

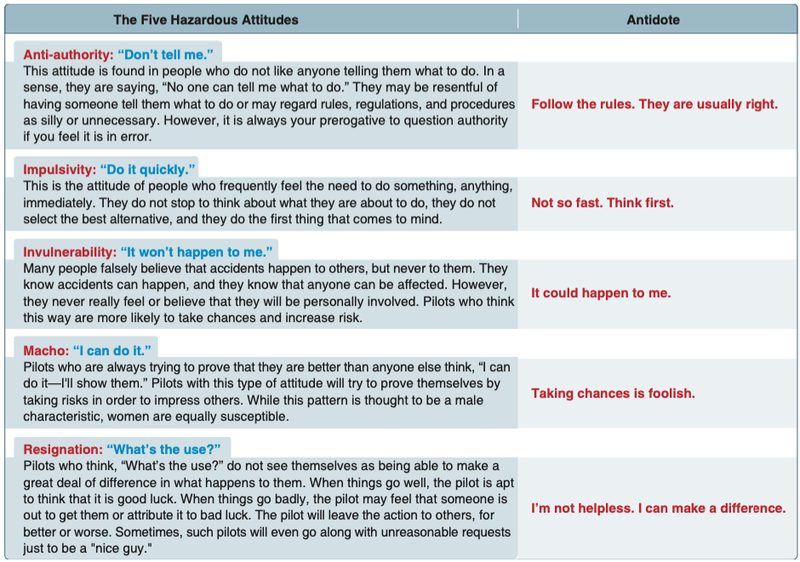

Sometimes the questions that the FAA focuses on in the Knowledge Tests and the Oral portion of the practical tests seem a bit dumb. Who would take off when you know your engine isn’t working? Do we really have to know that 'get-there-itis' is a thing? Apparently the answer is yes. I can never figure out which of the hazardous attitudes apply to their scenrios, but in this case it appears that he exhibited characteristics of at least three.

The FAA also stresses the PAVE checklist. If you go for a checkride, the examiner will start off by asking you about it.

Another way to mitigate risk is to perceive hazards. By incorporating the PAVE checklist into preflight planning, the pilot divides the risks of flight into four categories: Pilot in-command (PIC), Aircraft, enVironment, and External pressures (PAVE) which form part of a pilot’s decision- making process.

This pilot ignored the both the Aircraft and External pressures part of the checklist. The aircraft was clearly unairworthy and his desire to satisfy a specific personal goal (“get home-itis,” “get-there-itis,” and “let’s-go-itis”) was a major factor in deciding to take off.

Fortunately for everyone on the ground, the aircraft crashed into a parking lot next to a FedEx building and no on on the ground was injured. But this does bring up another point. Even though the likelihood of an engine failure is small, plan what you will do before taking off on every flight. It is somewhat puzzling as to why he crashed into a parking lot when there were empty fields all around him.

Fly the airplane all the way to the crash site.

A few of our members have had airplane crashes. On February 12, 2013 David Dickey was testing his Hummel H5 that he had built when it made a forced landing into a riverbed.

According to his statement to Kathryn’s Report

his amateur aircraft's engine stopped working, right as he was entering Atascadero. Dickey said there was no time for fear to sink in. After notifying the Paso Robles Airport that he needed to make an emergency landing. The next thing he thought of, after he realized he could no longer fly the plane, was where to land it.

"And then I noticed the power lines were draped all over the place, so I went ahead and decided to take an in, and my straight in shot was in the, what I thought was the sandy shore river. Unfortunately it was the sandbar. Not unfortunately, because I did a good landing and I got down safely," said Dickey.

CFIT - Controlled Flight into terrain.

In 1989 The pilot departed San Luis Obispo airport on a planned flight to Santa Barbara. The wx was VFR at SBP but there was fog around the coastal area. Abt 9 minutes after departing SBP ground witnesses heard the airplane's engine in the vicinity of the crash site and the engine sound abruptly stopped.

Another CFIT accident happened a few days before my checkride when During the instrument flight rules initial climb after takeoff, in fog, to visual conditions on top, the airplane collided with the ground about 1 mile from the departure runway. Prior to departure on runway 11, the pilot contacted the control tower to request the instrument departure to on-top and was advised to standby. During the course of communication the pilot was advised the "tops" were 300 feet above ground level, and was issued a clearance to taxi to the runway. The tower advised the pilot that they were closing and to contact ARTCC for release. The pilot obtained the IFR clearance and was released to on-top. The pilot's release included a standard instrument departure that required a right turn to 130 degrees after departure. The pilot of this airplane was an ATP and CFI so it is really puzzling as to why he couldn’t fly a few hundred feet to VFR-on-top. No mechanical fault was found with the aircraft.

I couldn’t find details of another CFIT accident in the database, but Jim Raticheck confirms my recollection of the details so I broadend my search to San Luis Obispo instead of SBP and found it. In September of 2000 a newly-minted pilot flew with his girlfriend from Fresno to San Luis Obispo for the day. The non-IFR rated pilot, who had only a few hours under the hood, took off on runway 11 to return to Fresno. He immediately entered fog and while attempting to return to the airport, crashed in a vinyard just off the end or Rwy 11 due to spacial disorientation. The girlfriend died. This appears to be another example of get-there-itis since news reports suggested that he made the decision to depart into the fog because he knew the girl’s father would be upset if he stayed overnight with her in San Luis.

The IFR charts show Islay Hill at 791' just north of the airport and none of the approaches allow circling north of the runway. Nevertheless, the non-instrument rated pilot took off on Rwy 11 on a dark night with low clouds. According the NTSB report The pilot had received his private pilot certificate the preceding month, at a total flight time of 69.6 hours, including 3.5 hours at night.… the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The pilot's continued flight into instrument meteorological conditions, and his failure to maintain clearance from the rising hilly terrain. Contributing factors were the pilot's inexperience regarding flying during the dark, nighttime condition, and the low ceiling.

I’ll leave to the reader the exercise of deciding which of the Hazardous Attitudes and PAVE checklist items were in play here and only note that according to §91.103 Preflight action. Each pilot in command shall, before beginning a flight, become familiar with all available information concerning that flight.. While it is unreasonable to expect that a newly-minted pilot should be familiar with the IFR approach charts for an airport, and the hill does not appear on the sectional, at a minimum a pilot should know that an overcast ceiling of 800' would not allow them to get over the hills to the north of the airport.

Mid-air collision

Most mid-air collisions occur around an airport in day VFR conditions. This one was no exception. At about 11:18, a Beech C-99 (Wings West Flt 628), N6399U, & a Rockwell 112TC, N112SM, collided in midair aprx 8 mi west-northwest of the San Louis Obispo County arpt. The Rockwell 112TC had departed Paso Robles, CA & was descending toward the San Louis Obispo County arpt. The Beech C-99 had departed San Louis Obispo & was climbing on a flt to San Francisco. They collided head-on at about 3400 ft MSL in clear wx. The C-99 crew had just contacted Los Angeles artcc. At that time, the aircrews of both acft were governed by the 'see-and-avoid' concept with regard to each other. An investigation revealed that the standard departure & instrument apch procedures shared a common track. The C-99 was departing along the departure track. Just prior to the collision, the 112TC crew had contacted unicom & reported at the dobra intersection which was on the ILS apch course. After colliding, both acft crashed on open terrain & burned. The controller had only seconds to appraise radar data & issue a safety advisory.Apply Carb Heat quickly.

Carb icing isn’t an issue with the fuel injected planes that I fly and the Cherokee isn’t know for having carb icing issues, but lots of planes are, especially older low-powered aircraft. The FAA has a few pages in the January/February 2017 Safety Briefing talking about how to recognize when conditions are ripe for carb icing.

I don’t remember this accident when an Aeronca crashed into trees on the Cal Poly campus, but Kurt Colvin was in the air with a student when it happened. The student reported that, He was banking right to go to the soccer fields, (but) I think he saw someone (on the fields) and saw there was a field to his left,” West said. “He banked to make the turn to his left, but he was low, so he crashed into some trees. It looked like his left wing hit the tree first, so his nose was swinging left. It looked like he rotated almost 180 degrees, and also his tail went up over him. The probable cause was The pilot’s delay in using carburetor heat, which resulted in a loss of engine power due to an encounter with carburetor icing conditions.

The conditions for this accident fell within the range of serious icing at cruise power. The FAA’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge states that application of carburetor heat will cause a further reduction in power, and possibly engine roughness as melted ice goes through the engine. It states that these symptoms can last from 30 seconds to several minutes, depending on the severity of the icing.

If you wait to pull carb heat until the engine has actually quit, it will be too late for the heat exchanger to melt the ice. That means the likelihood of getting power back is pretty low if you don’t catch the ice buildup early. Sometimes descending to a lower altitude where the air is warmer works, but terrain has to allow for that. The bottom line is if you think you might be getting ice, pull carb heat, watch for an rpm drop, which is followed by a rise. The engine might run rough for a little bit.

I also don’t remember this 2005 accident and Kurt Colvin reported that he didn’t remember the details of his landing in a Cal Poly soccer field, the NTSB determined that the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: a loss of engine power due to carburetor icing and the pilot's failure to use carburetor heat.

There’s a reason the FAA harps on “buzzing”

The pilot in this accident was in violation of several FARs. According to the report, Witnesses reported that they observed the airplane flying low above the beach before it ascended abruptly. When the airplane was about 150 to 200 feet above the ground, the ascent stopped, and the airplane then descended in a nose low attitude to ground impact. Witnesses also reported that the engine sounded normal during the accident sequence. Postaccident examination of the airframe and engine revealed no preimpact mechanical malfunctions or failures that would have precluded normal operation.

In the probable cause determination the NTSB said that The pilot had a reported history of marijuana abuse. Toxicology testing on the pilot was positive for tetrahydrocannabinol at levels that indicate he was likely impaired during the flight. This impairment likely affected the pilot’s ability to maintain airplane control and his decision to begin a low-level flight maneuver at an altitude that was not sufficient for recovery before impact with the ground.

i4 CFR §91.119 Minimum safe altitudes: General.

no person may operate an aircraft below the following altitudes:

(a) Anywhere. An altitude allowing, if a power unit fails, an emergency landing without undue hazard to persons or property on the surface.

(b) Over congested areas. Over any congested area of a city, town, or settlement, or over any open air assembly of persons, an altitude of 1,000 feet above the highest obstacle within a horizontal radius of 2,000 feet of the aircraft.

(c) Over other than congested areas. An altitude of 500 feet above the surface, except over open water or sparsely populated areas. In those cases, the aircraft may not be operated closer than 500 feet to any person, vessel, vehicle, or structure.

§91.17 Alcohol or drugs.

(a) No person may act or attempt to act as a crewmember of a civil aircraft—

(3) While using any drug that affects the person's faculties in any way contrary to safety; or

So he was clearly violating the rule about being at least 500' above people and using a drug that impaired his ability to fly. Refering back to the FAAs hazardous attitudes checklist, he was exhibiting behaviour of at least three—antiauthority, macho, and invulnerability.

Taxiing takes full concentration

On the day before my private checkride I was taxiing out for takeoff and these two planes were still in the runup area after the Cessna T201L taxied into a Cessna 310 in the runup area.

On January 15, 2001, at 0730 hours Pacific standard time, a Cessna T210L, N2508S, and a Cessna 310, N890GR, collided on the ground in the run-up area for runway 29 at San Luis Obispo Airport, San Luis Obispo, California. Both airplanes sustained substantial damage. The Cessna T210L was operated by the private pilot/owner, who was not injured, as a business flight under the provisions of 14 CFR Part 91. The Cessna 310 was rented by a commercial pilot for a business flight under 14 CFR Part 91, and neither he nor his passenger were injured. Visual meteorological conditions prevailed, and both airplanes were preparing to depart. The Cessna T210L pilot had filed an IFR flight plan to Palomar, California, and intended to receive his clearance airborne. The Cessna 310 pilot intended to fly VFR to Santa Monica, California, and no flight plan was filed.

Both pilots were interviewed by Safety Board investigators. The pilot of the taxing Cessna T210L stated that the morning sun restricted his vision to the point that he did not see the Cessna 310 in the run-up area. The pilot of the Cessna 310 stated his airplane was stationary and he was looking inside performing prop governor checks and at the last second saw a "white flash" in the corner of his eye.

The right wing of the Cessna T210L was severed approximately 6 feet inboard of the wingtip when it contacted the right propeller of the Cessna 310. The Cessna 310 suffered damage to the right propeller, engine, right wing fuel tank, and sudden engine stoppage.

Don’t rush your takeoff checklist

Jims Sabovitch had flown his 310 to Catalina for lunch with some friends. While dining, the pilot noticed that the weather was deteriorating rapidly and suggested that they depart before instrument meteorological conditions prevailed. After boarding the airplane and starting the engine, the pilot conducted an abbreviated engine run-up during the taxi. The takeoff roll was normal, but about 2 to 3 seconds after liftoff, the left engine failed, and the airplane veered to the left. The pilot pushed the nose down to maintain airspeed, and the airplane entered a cloud/fog bank, impacted terrain, and was engulfed by fire.

The NTSB report of Probable Cause and Findings stated that the probable cause(s) of this accident to be:

The pilot's improper setting of the left engine fuel selector valve, which resulted in fuel starvation of the left engine immediately after takeoff. Contributing to the accident was the pilot's decision to try to depart ahead of developing weather, which resulted in his hastened departure procedures and likely led to his failure to recognize the incorrect fuel selector positioning.

WTF?

One of the most bizarre accidents occurred on April 28, 2017 when the pilot apparently attempted to hand-prop his Mooney and it knocked him over and ended up in the grass by the runway. This one didn’t make it into the NTSB database, but Kathryn’s Report has a few details. If he was intentionally trying to hand prop a Mooney by himself, that’s pretty dumb. The newspaper reported that the pilot was trying to turn the engine over manually to fix a stuck propeller. If that was the case, then making sure that the mags are off and the key is on the dashboard is imperative. Even so, this ranks up there with the Cessna 337 accident in ignoring the PAVE checklist. I have heard of pulling the prop through a couple of times on very cold days to unstick the cylinders but if the prop won’t move and you do get it loose, do you really want to go flying without first figuring out what caused it to be stuck in the first place?